What is a General Ledger? Everything You Need to Know (With Examples)

Justin (Do San Myung) is Expert Accountant at DualEntry with 20+ years of hands-on experience managing general ledgers, financial close processes, and ERP implementations for mid-market and enterprise companies. As a former Consulting CFO and Controller, he has personally overseen month-end closes, SOX compliance programs, and multi-entity consolidations across technology, manufacturing, and services industries. Justin specializes in transforming manual accounting workflows into automated, AI-driven processes.

Santiago is the co-founder of DualEntry. He previously co-founded Benitago, a digital consumer products group that raised $380 million in funding, grew to over 300 team members, and achieved $100M ARR over 8 years before its acquisition in 2024. Santiago has been featured in The Tim Ferriss Show, Forbes, The Wall Street Journal, and more. Originally from Venezuela, Santiago studied Computer Science at Dartmouth before leaving to launch Benitago.

%20(1).jpg)

The general ledger is the central hub for recording all financial transactions within an organization. It's essentially the master record that contains every debit and credit that flows through the accounting system. The GL serves as the primary source document for generating financial statements and maintaining compliance with SOX Section 404 internal control requirements.¹

According to APQC benchmarking, the median time to complete the monthly financial close is 6.4 days. Top-performing organizations close in 4.8 days or less, while those in the bottom quartile take 10 or more days. ² The difference impacts everything from management reporting to audit readiness. The general ledger pulls data from various ERP modules – AP, AR, inventory, fixed assets – and consolidates it into a single source of truth.

According to the PCAOB’s 2023 inspection report, approximately 46% of audits reviewed had at least one significant deficiency, including frequent issues related to journal- entry testing and general- ledger controls. ³ These problems cascade through the entire financial reporting process. This guide examines the core components of the general ledger, how to organize it effectively, common pitfalls to avoid, and how modern automation is changing GL management.

What is a general ledger?

.jpg)

According to the AICPA, the general ledger is defined as the systematic record of all accounting transactions for an organization.⁴ This comprehensive accounting record serves as the foundation for financial reporting under generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP).⁵ The GL consolidates transaction data from subsidiary ledgers and direct journal entries to create a complete financial picture.

The general ledger:

- It's a business main accounting record, containing all financial transactions

- Is a central repository where journal entries are posted

- Generates a business financial statements

- Is an audit trail documentation system

According to best practices, the GL typically integrates with AP, AR, inventory, and fixed asset modules to maintain data integrity. Without proper integration, you're looking at reconciliation nightmares every month-end. The system captures debits and credits from source documents, accumulates balances by account, and generates trial balances for financial statement preparation. Organizations rely on the general ledger for regulatory reporting, management analysis, and external audit requirements under SOX 404.¹

To understand the difference between the general ledger and its supporting subledgers — and why discrepancies happen in reconciliation — see our detailed comparison of general ledger vs subledger.

How does the GL stay organized?

The general ledger is organized through a chart- of- accounts (COA) structure a financial filing system (and if you need a structured starting point, use a free general ledger template). Standard COA numbering conventions typically use 1000s for assets, 2000s for liabilities, 3000s for equity, 4000s for revenue, and 5000-6000 for expenses.⁴ Most mid-sized companies need at least a 5-digit account structure, though enterprise systems can handle up to 10 segments.

The chart of accounts includes:

- Natural account segments (your main GL accounts)

- Cost centers for allocation

- Department codes for tracking by business unit

- Project tracking (if you run projects)

- Custom dimensions – so you can- add whatever you need

- Intercompany segments for multiple entities

Organizations typically structure their COA with natural accounts as the primary segment, followed by department and project codes. The natural account tells you what type of transaction it is, while departments and projects tell you where and why. Without proper segmentation, you're basically trying to run financial analysis with one hand tied behind your back. Companies usually go with 5 or 6 digits for their account numbers.

Example

Here's a typical purchase transaction posting:

Dr. Raw Materials Inventory (1310) $50,000

Cr. Accounts Payable (2100) $50,000

The GL automatically updates the running balance for both accounts. Account 1310 increases by $50,000 while your AP balance goes up by the same amount. The system maintains these T-account balances in real -time.

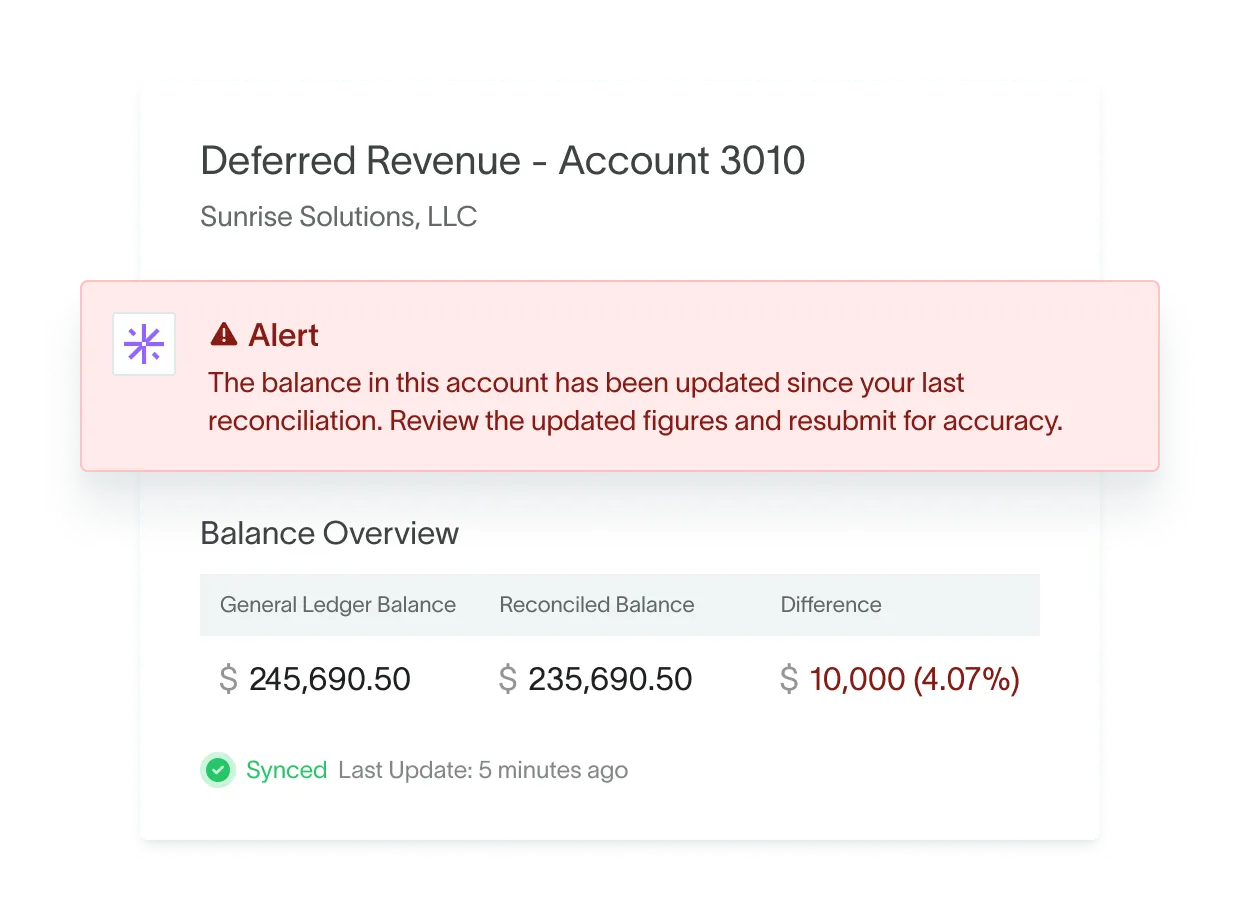

A more complex example

For reconciliation purposes, your GL control account needs to match the subsidiary ledgers. So if your GL shows $275,000 in AR (account 1200), your AR subledger should show $275,000 too. Organizations establish investigation thresholds through a risk-based account reconciliation policy to prioritize resources on high-risk accounts. For GL control account reconciliations to subsidiary ledgers, most organizations require zero variance or only immaterial differences based on their materiality policies.

How double-entry bookkeeping makes your GL work

Double-entry bookkeeping ensures your general ledger stays balanced through the fundamental accounting equation: Assets = Liabilities + Equity. Every transaction requires equal debits and credits. ⁷ Luca Pacioli first published detailed guidance on double-entry bookkeeping in 1494, though the system dates back to 13th-century Italy.

The double-entry system provides these controls:

- Every transaction requires equal debits and credits

- The accounting equation (A = L + E) stays balanced continuously

- Trial balance must equal zero

- Automated validation prevents unbalanced entries

- There’s a complete audit trail for all postings

The system enforces the accounting equation in real -time. When you debit cash for $10,000, something else needs a $10,000 credit – maybe you're reducing a receivable or recording revenue. The GL literally won't let you post an unbalanced entry. This validation happens at journal-entry level before anything hits the general ledger. SOX 404 requires that organizations establish these controls for public companies – including segregation of duties, so the person entering transactions isn't the same one approving them.¹

Without double-entry bookkeeping, you'd have no way to catch errors systematically. A single-entry system (like just tracking cash in and out) misses the complete picture. You need both sides of every transaction to understand what's really happening in your business.

Example

Here's a payroll entry showing multiple debits and credits:

Dr. Salary Expense (6100) $85,000

Dr. Payroll Tax Expense (6110) $12,750

Cr. Cash (1000) $97,750

The system blocks this if debits don't equal credits. Try to post $97,740 in credits? You’ll get an error message. The automated controls won't let it through because the entry must balance to be posted successfully.

What's inside your general ledger: the key components

The general ledger has multiple account categories that capture different types of financial transactions. Organizations structure their GL to accommodate balance sheet accounts, income statement accounts, and specialized account types that support specific business processes. The chart of accounts provides the framework for organizing these components into a logical hierarchy that makes reporting and analysis simpler.

Balance sheet accounts represent permanent accounts that carry balances forward from period to period. These accounts include assets, liabilities, and equity. Income statement accounts are temporary accounts that reset to zero at year-end. These include revenue and expense accounts.

The following account types make up the general ledger structure:

- Balance sheet accounts (permanent accounts that maintain running balances)

- Income statement accounts (temporary accounts)

- Statistical accounts for operational metrics

- Clearing accounts for month-end processes

- Suspense accounts for unallocated items

- Intercompany accounts for consolidated entities

The chart of accounts’ structure determines how organizations track financial data across multiple dimensions. Most mid-sized companies implement a multi-segment COA that allows reporting by legal entity, natural account, department, and project. The natural account segment identifies the type of transaction, while additional segments provide detail about organizational units and cost allocation. Without proper segmentation, financial analysis becomes limited to high-level account totals without visibility into underlying business drivers.

COA structure table:

A typical mid-sized company maintains 200-500 active GL accounts, depending on the business’ complexity. Organizations with multiple product lines or service offerings need additional account granularity to track profitability by business segment. The account structure should balance reporting requirements against maintenance overhead – excessive account detail creates reconciliation burden without analytical value.

Chart of accounts design requires consideration of reporting needs at implementation. Adding segments after go-live requires data migration and restatement of historical periods. Organizations should evaluate their COA structure based on management- reporting needs, regulatory requirements, and system capabilities. The natural account typically uses 4-5 digits, departments use 2-3 digits, and projects use 4-6 digits.

Here’s a mid-sized company example showing typical account volumes:

- 200-500 active GL accounts

- 15-25 departments

- 50-100 projects annually

- Monthly transaction volume: 10,000-25,000

Statistical accounts capture non-financial metrics that support operational analysis. These accounts track quantities like headcount, units produced, or square footage without corresponding dollar amounts. Statistical accounts appear in management reports alongside financial data to provide operational context for financial performance. For example, revenue-per-employee or cost-per-unit calculations need both financial accounts and statistical accounts.

Clearing accounts support month-end processing by providing temporary holding locations for transactions that haven’t been allocated yet. Payroll clearing accounts accumulate gross wages, taxes, and deductions before final posting to expense accounts by department. Bank clearing accounts reconcile book balances to bank statement balances. These accounts should zero out monthly, and persistent balances show unresolved reconciling items requiring investigation.

A more complex example

Accounts- receivable control account reconciliation shows the relationship between GL and subsidiary ledgers:

The AR subledger must reconcile to the GL control account 1200. Organizations typically carry out this reconciliation daily: it’s the best practice under SOX requirements to identify posting errors or interface issues between the AR system and the general ledger. ¹ Organizations establish investigation thresholds based on risk and materiality. For example, variances exceeding $1,000 or 1-2% of the account balance should be reviewed, while immaterial differences are documented and resolved monthly. All variances need investigation and resolution before month-end. Without daily reconciliations, subledger variances compound and slow down the close.

From transaction to general ledger: how it actually works

The general ledger posting process follows a standardized workflow: from receiving the source document receipt to reconciling the final account. To ensure SOX Section 404 compliance and data integrity, organizations establish systematic procedures for transaction capture, approval, and recording. Multiple control points throughout this process prevent errors and keep complete audit trails.

Modern ERP systems automate portions of this workflow, but manual oversight is still necessary for complex transactions.

The following steps outline the standard GL posting process:

- Source document is received and validated against purchase orders or contracts

- Journal entry is prepared, with supporting documentation attached

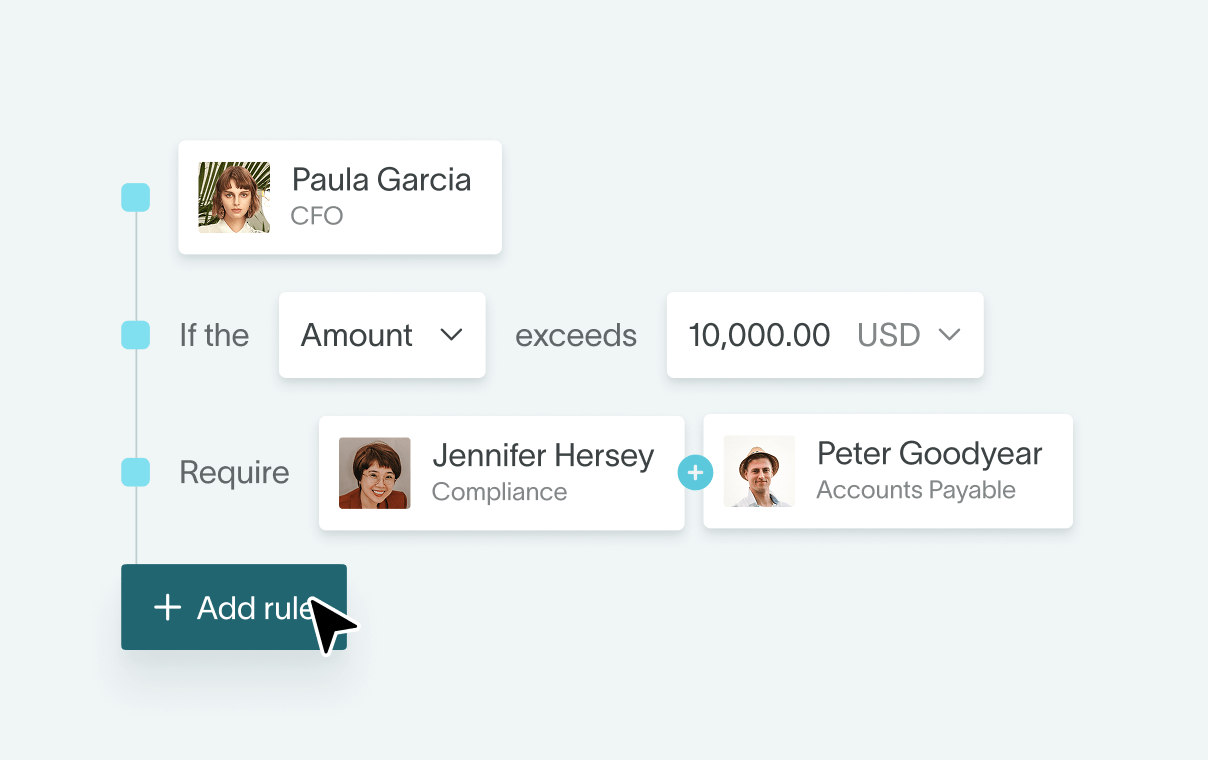

- Approval workflow is executed (according to a company’s specific guidelines, often based on dollar thresholds)

- GL posting takes place through batch processing or real-time integration

- Trial balance is updated and validated for debit/credit equality

- Reconciliation and review are handled by accounting management

This trial balance acts as the structured checkpoint before financial statements are prepared. If you want a clearer side-by-side explanation of how it differs from the general ledger itself, see our guide on general ledger vs trial balance.

Process flow: Source document → Journal entry → Approval → GL post → Reconciliation

The approval workflow calls for segregation of duties between transaction initiators and approvers. Authorization matrices typically establish dollar thresholds where transactions under $5,000 need supervisor approval, $5,000-$25,000 need manager approval, and amounts exceeding $25,000 need controller or CFO approval. These thresholds vary based on an organization’s size and risk tolerance.

The posting process requires three-way matching for purchase transactions - matching the purchase order, receiving document, and vendor invoice. Organizations must maintain documented approval trails and timestamp all postings for audit purposes. Batch posting cutoffs are typically at 4:00 pm EST every day, which ensures same-day processing while allowing enough time for error correction before the daily close. Cash transactions generally post in real time because of bank integration requirements and the need to keep position reporting accurate.

Here’s an example transaction workflow:

Customer Payment: $15,000

Approval: Controller approval required (exceeds $10K threshold)

Posting: Same day (if received before the 4pm cutoff)

Documentation: Remittance advice, bank deposit slip

Approval-threshold configuration requires balancing control requirements with operational efficiency considerations. Thresholds set too low result in approval bottlenecks and delayed transaction processing. However, thresholds that are too high increase a company’s exposure to unauthorized transaction risk. Organizations typically review their authorization matrices annually, updating thresholds based on business growth, inflation adjustments, and materiality assessment changes.

If you want to see more examples check our article: Real-Life General Ledger Examples (With Entries)

Why your general ledger actually matters (beyond compliance)

The general ledger is as more than a regulatory requirement under SOX Section 404.¹ Organizations rely on GL data for bank covenant calculations, management reporting, and strategic decision-making. Research suggests companies with well-maintained general ledgers complete their financial close in 6.4 days on average. Organizations with GL issues, meanwhile, need 10+ days or more to complete their close. ² This efficiency difference impacts reporting timeliness, audit costs, and management's ability to access up-to-date financial information.

The GL provides critical business functions beyond compliance, like:

- GAAP reporting accuracy per ASC 210 standards ⁹

- Bank covenant calculations for debt agreements

- Timely, accurate reporting for management

- Audit readiness, which can reduce external audit scope and associated fees

- Preparation of tax returns and IRS-required documentation

Financial institutions need accurate GL data for loan covenant monitoring. Most debt agreements include financial ratios calculated from GL balances. Common examples include debt-to-equity ratios, current ratios, and interest coverage ratios. GL errors can trigger technical covenant violations even when the underlying financial position remains sound – so organizations need to keep their GL accurate to avoid unnecessary covenant renegotiations or waiver requests.

GL data integrity is key for the audit process. External auditors sample transactions from the general ledger, test account balances, and evaluate internal controls over financial reporting. Proper documentation in general ledgers helps reduce audit scope and the fees associated with external audits.

Management reporting depends on timely and accurate GL data. Executive teams need current financial information for strategic planning, performance evaluation, and operational decisions. Financial close delays postpone management reporting and reduce the usefulness of financial data for decision-making. GL maintenance procedures should support monthly closes within 5-7 business days to make sure management receives actionable, up-to-date financial information.

Tax compliance requires detailed GL records that support tax return positions. The IRS mandates 7-year retention of accounting records. ¹⁰ The GL is the primary source document for tax return prep and audit defense. Proper account classification in the GL simplifies tax return preparation and reduces the risk of filing errors. Organizations need to maintain GL documentation that supports compliance with relevant ASC standards for revenue recognition (ASC 606), expense recognition, and asset capitalization, as well as SOX Section 404 requirements for financial reporting controls. ¹¹

Common general ledger problems (and how to avoid them)

General ledger errors create cascading problems throughout the financial reporting process. Companies must set up preventive controls and detective procedures to identify and correct GL issues before they impact financial statements.

The most frequent general ledger problems include:

- Misclassification errors (wrong account coding)

- Unreconciled accounts beyond 30 days

- Undocumented timing differences

- Manual journal entries without support

- Duplicate postings from interface issues

- Suspended or clearing accounts not zeroed

Misclassification errors happen when transactions post to incorrect GL accounts. Under ASC 842, coding operating leases as finance leases results in front-loaded expense recognition instead of straight-line patterns. Revenue posted to liability accounts understates income and overstates obligations. Organizations should set up coding validation rules that restrict valid account combinations - segregating lease accounts (1280-1295) from fixed assets (1200-1299) and flagging unusual postings for review. Chart- of- accounts training for non-accounting staff, focusing on lease classification, can reduce coding errors at the source.

Unreconciled accounts are one of the highest-risk GL issues. Accounts receivable variances between the GL control account and AR subledger indicate missing transactions or posting errors. A variance of $50,000 in AR requires immediate investigation to determine whether the error affects revenue recognition, cash application, or credit- memo processing. Daily reconciliation requirements prevent small variances from accumulating into material misstatements.

Most GL errors come from manual journal entries. Entries without supporting documentation create audit trail gaps and increase restatement risk. Companies must enforce policies requiring scanned backup documentation to be attached to all manual entries. Approval workflows should route entries that exceed materiality thresholds to controllers or CFOs before posting.

Duplicate postings typically result from interface failures between subsidiary systems and the general ledger. Vendor invoices posting twice from the AP system create overstated liabilities and expenses. System controls should validate invoice numbers against prior postings and block duplicate entries. Regular review of duplicate payment reports identifies overpayments requiring recovery.

Real examples with implemented solutions:

- Operating lease in wrong account → Implement coding validation rules restricting valid account ranges

- AR variance of $50K unresolved → Daily reconciliation requirement with documented variance investigation

- Duplicate vendor payment of $25K → Enhanced system controls validating invoice numbers before posting

Review frequency by account type:

Clearing and suspense accounts require special attention during month-end close. These accounts should zero out monthly, and persistent balances indicate unresolved items. Payroll clearing accounts with balances after month-end suggest payroll allocation errors. Bank reconciliation clearing accounts with aged items indicate outstanding checks or unrecorded deposits requiring investigation. Review procedures should flag any clearing account with a balance that exceeds $1,000 or is 30 days old.

Timing differences between recognition and cash flow create reconciliation challenges. Accrued expenses that are recorded in one period but paid in the next need careful tracking to prevent duplicate recording. Prepaid expenses must be monitored to ensure proper amortization over the benefit period, per accrual accounting principles and the matching principle. Companies should maintain detailed schedules and support all accruals and prepaids with monthly review by accounting management.

General ledger software and AI automation: what's changed

Cloud-based general ledger software has transformed how organizations manage financial data and accounting processes. Modern GL systems integrate artificial intelligence capabilities to automate transaction coding, reconciliation, and anomaly detection. According to vendors surveyed in the CPA.com 2025 AI in Accounting Report, AI-powered workflow automation for accounting tasks results in time savings between 30-70%, and organizations see up to 70% less time spent on manual tasks. According to the AICPA and the CPA.com 2025 AI in Accounting Report, agentic AI is increasingly used to automate reconciliation and accelerate workflow triage.¹² Automation capabilities reduce close cycle times and improve data accuracy across financial reporting.

AI-powered GL software has the following capabilities:

- Automated transaction coding (using ML algorithms)

- Real-time posting capabilities

- Integrated reconciliation modules

- Anomaly-detection algorithms

- Journal-entry creation using natural language

Traditional general ledger systems needed manual transaction coding and periodic batch posting. Modern cloud GL platforms process transactions in real -time. These platforms apply machine learning models to categorize entries automatically. The system learns from historical coding patterns and suggests appropriate GL accounts based on transaction characteristics.This reduces the time accounting staff need to spend on routine data entry.

Reconciliation automation represents a significant advance in GL software capabilities. Traditional reconciliation called for accountants to manually match transactions between subsidiary ledgers and GL control accounts. AI-enhanced systems perform these matches automatically and flag variances that go over defined thresholds. Industry implementation studies indicate that organizations utilizing AI-driven reconciliation automation achieve approximately 34-57% reduction in month-end close processing time (compared to manual processes). ¹⁵ Finance professionals spend 20- 30% less time crunching data when AI tools are implemented, which allows them to focus on higher-value business partner roles. ¹⁶

Anomaly- detection capabilities identify unusual transactions that may indicate errors or fraud. The system establishes baseline patterns for account activity and flags transactions deviating significantly from expected ranges. For example, office supply expenses typically range between $2,000-$5,000 monthly, a $25,000 posting would trigger an automatic review. Detection algorithms improve over time, learning from a company’s data and transaction patterns.

Natural language processing allows users to create journal entries using plain English descriptions rather than complex coding structures. Users can describe the transaction in conversational terms, and the system translates this into proper debit and credit entries with appropriate account codes. This functionality reduces training requirements for non-accounting staff who occasionally need to enter transactions.

Technology capabilities comparison:

Integration capabilities allow GL systems to connect with AP, AR, inventory, payroll and other financial modules. These integrations eliminate duplicate data entry and ensure transaction data flows automatically into the general ledger. Organizations should evaluate integration options when choosing the best general ledger software, making sure it’s compatible with the business’ existing systems and future tech requirements.

Example implementation results from DualEntry AI show transaction categorization processing 10,000 transactions in 3 minutes (compared to 8 hours for manual coding). Industry sources indicate that organizations using automated GL coding systems in 2025 typically achieve accuracy rates of more than 95%. ¹³

Finance teams that implemented automation report 24% lower staffing levels than organizations that have not, according to APQC. ¹⁴ Different companies choose different strategies: some reduce headcount, while others maintain headcount but shift staff focus to analysis rather than data entry. Cost savings from reduced labor requirements typically offset software subscription costs within 18-24 months. Implementation costs, training requirements, and change- management factors should be considered when calculating ROI for GL automation projects.

How often should you review your general ledger?

General- ledger review frequency depends on account risk levels, transaction volumes, and regulatory requirements. SOX Section 404 establishes monthly review as the minimum requirement for material accounts. Organizations should implement differentiated review schedules based on account characteristics rather than applying uniform monthly reviews across all accounts.

Review frequencies by account category:

- Monthly minimum for all accounts

- Daily for cash and cash equivalents.

- Weekly for high-volume accounts

- Quarterly for low-activity accounts

Cash accounts need daily review because of their susceptibility to fraud and the high volume of daily transactions. Organizations must reconcile bank accounts daily to identify unauthorized transactions, processing errors, or fraudulent activity quickly. Daily cash reconciliation also ensures accurate cash position reporting for treasury- management and liquidity- planning purposes.

High-volume accounts such as AR and AP warrant weekly review. These accounts experience frequent posting activity that can obscure errors or irregularities. Weekly reviews allow accounting staff to identify and correct issues before they accumulate into material variances that require investigation. These reviews should include subledger reconciliation, aging analysis, and examination of unusual transactions or account movements.

Revenue and expense accounts typically need monthly review as part of the financial close process. The review validates account activity against budget expectations and identifies misclassifications or unauthorized expenditures. Controllers should establish materiality thresholds that trigger additional investigation – variances over 10% of budget, or over $10,000, typically call for detailed analysis, depending on an organization’s size.

Low-activity accounts – including certain fixed asset categories or long-term liability accounts – can be reviewed quarterly. These accounts have infrequent transactions and lower inherent risk. A quarterly review confirms that no unexpected activity occurred and validates that scheduled transactions, like depreciation or interest accruals, posted correctly.

Review frequency varies by company size and complexity:

- Small organizations (under $50M revenue) conduct monthly reviews at a minimum

- Mid-size companies ($50M-$500M revenue) review key accounts weekly

- Large enterprises (over $500M revenue) perform daily reviews of critical accounts

Documentation requirements mean that all GL reviews should include evidence of the review performed, identification of exceptions noted, and resolution of identified issues. SOX compliance requires reviewers to document their procedures and maintain evidence supporting review completion. Organizations without adequate review documentation face issues during future audits.

Automated review tools reduce the time needed for GL account analysis. Exception reports highlight accounts with unusual activity, with zero balances where activity is expected, or with transactions exceeding established thresholds. These reports allow reviewers to focus their attention on high-risk items rather than examining every account manually.